ADVENTURE

AIDS

AIRLINES

AIRPORT

AIRPORT BUS

ARCHAEOLOGY

ARCHITECTURE

ARCHIVES

ART GALLERIES

BANKS

BIRDING

BOOK EXCHANGE

BUDGET TRAVEL

BUSES

BUSHFIRE

BUSHMAN PAINTINGS

BUSHMEN

CAMPSITES

CAR HIRE

CARS and DRIVING

CATTLE

CLIMATE

COLONIALISM

CRIME

DRUGS

ECONOMY

HISTORY

IMMIGRATION

KINGS

MBABANE

NATURE RESERVES

POLICE

RITUAL CEREMONIES

SIBEBE TRAILS

TOUR COMPANIES

TRAVEL AGENCIES

Index to information in the guide

The embryo of the Swazi Nation arrived in the south of what is now Swaziland during the middle of the 18th century. They had spent the previous two hundred or so years at Catembe, near Maputo. After arriving they gradually subdued the Sotho speaking clans in the area, set about creating a regional power which extended far beyond the boundaries of present-day Swaziland.

The Zulus to the south were a formidable force, so the Swazis concentrated on expanding to the west and the north. The present day towns of Nelspruit, Barberton, Piet Retief, Carolina and others were part of Swazi territory for about 20 years.

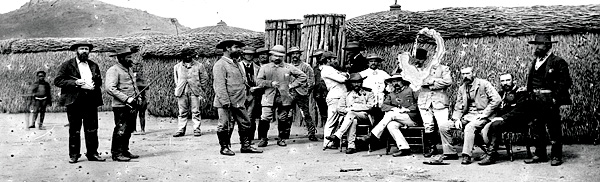

In 1879, during a time of gold-rushes worldwide, gold was discovered in Swaziland. The news of gold strikes quickly attracted large numbers of prospectors, far from the British ideal of good settler stock. Men initially attracted by gold, persuaded the King to grant them concessions for minerals, land, trade and monopolies in return for tribute.

The Swazi Kings helped the British in an alliance against the Pedi tribe in return for a guarantee of independence. However, when this promised independence faded, the Swazi King applied to the British to become a Protectorate to forestall possible attempts by Boer and Portuguese factions to incorporate Swaziland into their territories.

These fears were realised, when just before the Boer War, Transvaal Boers administered Swaziland and soon put the King on trial for murder. After the Boer War, Swaziland, as war booty from the defeated Boers, fell under British control and the colonial era started in earnest.

This was the start of a long-lasting dispute about land title in the country. In effect what was happening in Swaziland was also occuring worldwide, as colonial powers partitioned the entire Third World amongst themselves. It was possible to go along with this as the Swazi did, or to fight like the Zulu or many American Indians, but the outcome was the same: colonisation.

The British later transferred most land concessions into freehold land. Thus, in a matter of thirty years after the first arrival of large numbers of Europeans in Swaziland, the Swazi had been almost completely dispossessed of their land. During much of the twentieth century, attempts were made by both sides to rectify this, with varying degrees of enthusiasm.

The British made concession holders return one third of their acreage to the Nation in 1907 and reserved almost another third as crown land. Afterwards, King Sobhuza II also set up a fund to buy back land for the Nation, mainly funded by Swazi mine workers in Johannesburg. Over 65 percent of the country is now national land and, to varying degrees, is administered by Tibiyo or by chiefs who have discretion as to who farms the land. Their power is absolute.

Because Swaziland was a protectorate rather than a colony, a more indirect form of rule existed, where the King (the Paramount Chief to the colonial office) had a considerable amount of say in the internal running of the country, but none in its external affairs. Social segregation between the white settlers and the Swazi existed, but was never formalised in a legal code as was the case in South Africa with apartheid. This meant that a non-racial state became a reality without much fuss on September 6, 1968 when Swaziland regained her independence.

The British had bequeathed a Westminster-style constitution which King Sobhuza II repealed in 1973, after elections where three opposition members got seats and set about criticising the Government. For Sobhuza this went against two traditions; there was no consensus which was an important part of Swazi tradition, and his authority was being questioned. Sobhuza wished to have the constitution amended to one more appropriate to his view of Swaziland's culture which would take traditional values into consideration. The constitution was partially reinstated in 1978 and incorporated both traditional and Western laws and customs.

After King Sobhuza's death in 1982, the political scene was coloured by a palace feud which led to concern that an unstable political situation was emerging. A partial balance was restored on the coronation of King Mswati III in 1986. The King inherited a difficult situation at a young age: balancing the needs of a traditional monarchy with the needs of an increasingly industrialised and educated population who have different priorities.

This is a brief overview only - for more detailed accounts, see the Archaeology, Colonialism and Kings entries.